A bill to make education and safety classes mandatory for many boaters in Maine is working its way through the Legislature, but its fate is uncertain with lawmakers wavering on how to roll it out.

Maine is an outlier among states for not requiring boater education. In the late 1990s, a statewide task force recommended to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife that it implement required boater education on lakes and ponds, which if approved by lawmakers this year would be a major policy shift.

Starting January 2027, the proposed law would require a boater safety and education course for anyone:

• Supervising a child under age 12 who is operating a motorboat of more than 25 horsepower on inland waters;

• Ages 12 and older operating a motorboat of more than 25 horsepower on inland waters;

• Ages 16 or older operating a personal watercraft on inland waters.

“It’s going to give you some practical information. A lot of people would say, ‘Oh I already have that knowledge,’ and maybe they do, and maybe they don’t,” said Sen. Jim Dill (D-Old Town), who chairs the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Committee working on the legislation.

A group of state lawmakers voted unanimously in favor of the legislation in January. Yet they are now reconsidering and weighing whether to ask the department to instead convene a stakeholder group to modify the legislation. They are scheduled to discuss the proposal again Monday.

Still being considered is whether the proposed law should exempt some older adults from testing requirements or to expand the legislation to include tidal waters, Dill said.

The state cut the public and industries out of the legislative process, said the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine, an 8,000-member organization of hunters, anglers and trappers led by lobbyist David Trahan, and the Maine Marine Trades Association, which represents commercial and recreational marinas, boat builders and boat yards.

More boater education may ultimately be a recommendation of a stakeholder group, leaders of both organizations told The Maine Monitor. But the lack of public input — due to last-minute publishing of the bill’s text and its amendments — has made for an unfair public process.

The version of the bill that lawmakers voted for is not posted on the Legislature’s website.

“We’re supposed to have public input on policies like this and right now I bet no one out there in the general public, other than a few of us, know that there’s a mandatory boating education bill out there,” said Trahan, who was a Republican state lawmaker.

Optional boater education courses are already offered online or in person. The state recognizes four online courses and boaters would need to complete one to be certified under the proposed law. A six-hour, in-person course is also offered in Portland.

Rep. Jessica Fay (D-Raymond), who is sponsoring the legislation, spent her summers on Sebago Lake. Over time she has seen faster, heavier and bigger boats arrive on Maine’s lakes, ponds and rivers, she said.

There are at least 12 lakes and ponds in her legislative district, and she receives complaints from each about recreational boat usage, Fay said. Boat wakes are damaging private docks and eroding the shoreline, which can release nutrients from the soil into the water, and lower its quality and clarity. She’s seen personal watercraft strike loons, and experienced motorboats getting too close and rocking sailboats.

“You just wonder, does this person see me? Are they going to run me over?” Fay said. “And that’s not fun.”

Near-fatal encounters

Maine lags behind other states by not requiring boaters to complete an educational course before operating a motorized boat or personal watercraft, state officials said.

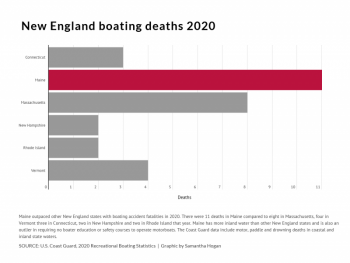

There were 11 deaths from boating accidents in Maine in 2020, according to statistics gathered by the U.S. Coast Guard, that include motorboats, paddle watercraft, and drownings on and around boats.

By comparison, New Hampshire reported two deaths from boating accidents in 2020, according to the same data. New Hampshire law requires boaters age 16 and older, who are operating a boat of 25 horsepower or more, to have completed a similar education course to the one proposed in Maine.

Other New England states also reported fewer boating deaths than Maine in 2020. Rhode Island reported two deaths, Connecticut reported three, Vermont reported four and Massachusetts reported eight, according to the U.S. Coast Guard data.

Maine has the most inland water of the six New England states, according to federal data.

Maine is also unique in that its inland waters are used predominantly for recreational boating while its coastal waters are dominated by commercial fishing, said Col. Dan Scott, the head of the Maine Warden Service, the state’s law enforcement branch for inland boating.

During 2020, the first year of the pandemic, the state saw an increase in boating, Scott said. The state’s waters are public and as more people begin boating, state officials believe it’s a good idea for people to know the laws and be informed of their effect on the environment and other boaters.

“There’s also many, many pages of ‘rules of the road’ and ‘rules and regulations’ that if you purchase a boat and don’t go seek them out on your own, you’ll never even know they exist,” Scott said. “Like everything else, the pandemic brought this to light.”

Roland Constable of Belgrade was struck by a boat while scuba diving a few feet below the surface of North Pond in Smithfield in June 2021. His right arm and shoulder were hit by the boat’s propeller.

“I was still fairly new to scuba diving and all of a sudden I heard ‘bang,’ and the boat hit me in the head and ran over me, and shot me out the back of the boat,” said Constable, who was cleaning cans and golf balls from the bottom of the lake and had his location marked with a “diver-down” flag. “That’s when the propeller caught me on the right arm.”

The collision pulled the regulator, which he used to breathe, from his mouth. His arm went numb and he couldn’t control his scuba equipment. The operator and passengers on the boat pulled Constable from the water.

The boat hit him while the people on board were trying to retrieve a stray buoy, which was actually a diving flag Constable posted on the surface. The red flag with a white horizontal line is briefly described in the state’s guide for boaters as the signal there are divers or snorkelers beneath the surface.

“The biggest thing was they had no idea what the flag meant. They just thought it was a loose buoy floating around the water,” Constable said.

The accident could have easily turned fatal. While swimming in Damariscotta Lake in 2018, Kristen McKellar was struck by a boat and injured by its propeller. She died of her injuries, the Bangor Daily News previously reported. Separately, a 17-year-old operating a personal watercraft hit a boat, killing Ryan Conary of Sanford and injuring a 13-year-old in 2020, news outlets reported.

Constable said required boater education was likely a step in the right direction. He would like the state to also improve its education about divers and amend laws to keep a safe distance from diver-down flags.

The accident hasn’t kept Constable out of the water. He continues to scuba dive.

A solution for everyone

The proposed legislation seeks to address a variety of complaints the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Committee were asked to consider regulating in recent years, including Jet Ski use, invasive species and the “rules of the road” on Maine waters, Scott said.

“During every one of those conversations, it came back to, ‘Well, we also need to educate boaters.’ It’s always enforcement and education,” Scott told lawmakers.

The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife plans to tailor parts of the online courses to address Maine specific concerns about invasive aquatic plants, erosion and wildlife. There is an exam at the end of the course, which boaters must pass to receive a certificate.

Boaters of all ages must meet the education requirement if the legislation becomes law as currently drafted. Yet, lawmakers are wavering on whether to allow some adult boaters to continue to operate without a certificate.

“At the end of an education course there’s a test, and I think that scares most people. If you haven’t been in school for 10 years or longer, thinking you have to pass a test to operate a boat that you’ve been operating for 10 or 20 or 30 years is probably a little unnerving,” said Dill, the state senator.

Some state laws grandfather in boaters born prior to a certain year. A prior version of Maine’s draft legislation included an exemption for anyone born before Jan. 1, 2002 — effectively exempting everyone over age 20 from the new law.

It will take decades, rather than the five years proposed by the draft law, to educate the state’s boaters if it is phased in based on birth year, said Scott during a recent legislative meeting.

Nationally, nearly two-thirds of boating fatalities occurred with an operator age 36 or older, according to the U.S. Coast Guard data for 2020. Maine aligns with national trends, Scott said.

Teenagers driving boats accounted for less than 3% of boating deaths nationally in 2020, and children 12 and under operating boats represented 0.3% of fatal boating accidents, according to the Coast Guard.

“Those statistics are telling,” said Fay, the bill’s sponsor. “Like with cars, everybody takes a driver’s test and everybody has to get a license. We’re not going to probably solve boating accidents this way, but I think education is a really good first step.”

Fay would be among those required to complete the course if the law is passed. She has taken courses but not the final exams required to get the certificate, she said.

“The most important thing is to start somewhere. Maine is generally a leader on this stuff and it is really interesting to me that other states have been doing this for a long time, and that we’ve resisted,” Fay said.

Out-of-staters operating boats on inland Maine waters will be expected to have passed a nationally recognized boater education class. The state plans to accept out-of-state boating licenses from nationally recognized programs as well as Canadian Pleasure Craft Operator Cards. There is a carveout in the legislation for Maine Guide license holders who have met the requirements to carry passengers for hire and boaters who already hold a maritime license.

The bill intentionally sets the floor at 25 horsepower motors to exempt recreational fishermen, who may be operating light aluminum boats with 9.9 to 15 horsepower tiller outboard engines, Scott said. These boaters would not need to take a course or pass a test, according to the legislation.

Mandatory education wouldn’t be a complete solution, said Trahan on behalf of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine.

“I can guarantee you that an education course is not going to solve the problem alone. People will see it as nothing but an obstacle to getting their boat registration. They’ll do it but they won’t comprehend it. You’ve got to have, I think, a more comprehensive approach to this problem,” Trahan told The Maine Monitor.

“If we really think that an education class is going to solve our problems, then I think we’re leaving a real solution on the table.”

Enforcement needs to be expanded, he said. He proposes that the state look at raising the boat registration fee to expand enforcement of boating laws, or add a tip line for boaters to report unsafe boat operators, instead of requiring courses and exams paid to private businesses, Trahan said.

There are approximately 40 game wardens working across the state on any given summer day to enforce and respond to boating, nuisance wildlife, hunting, fishing and ATV complaints, Scott told The Maine Monitor.

The state also hires four part-time deputies to supplement boating enforcement, primarily in the southern part of the state, Scott said at a legislative meeting. The state spends several thousand hours on the water each year, and issues summons and warnings to boaters. It also conducts between 10,000 and 20,000 boat inspections a year, he said.

“We spend a significant amount of time enforcing boating related laws,” Scott told lawmakers.

The state intends to charge a civil violation between $100 and $500 for operating a boat without having completed a safety and education course, according to the draft law. If a court finds that a person repeats the violation three or more times within five years, a misdemeanor has been committed.

Tidal waters

As written, only boaters on inland waters would need to abide by the law change. Commercial fishing boats and boaters on Maine’s coast would not be affected.

The decision not to apply the education requirement to boaters on tidal waters is due in part to increased boating traffic and pressure along with “more shenanigans and kind of irresponsible behavior on inland waters” that is not seen on the coast, Commissioner Judy Camuso of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife said at a recent legislative hearing.

Stacey Keefer, executive director of the Maine Marine Trades Association, said there’s a concern that the state would send an unintended message that boater safety is more important on inland than tidal waters by not also mandating certification on coastal waters.

“Saltwater boating includes many of the same risks, but also many more challenges and hazards with coastal Maine tides, fog, commercial traffic and cold water,” Keefer told The Maine Monitor.

State officials acknowledged that the National Association of State Boating Law Administrators, or NASBLA, questioned them about why coastal waters were not included in the state’s draft law. The exclusion of tidal waters was done to avoid writing multiple exemptions into the new law.

Education for boaters on Maine’s coastal waters is one of the gaps that could be considered by a stakeholder group if one is formed, Dill said. He said he hoped the Legislature would take a first step by passing a law to mandate education for boaters on inland waters.

As drafted, the legislation lays out the implementation date five years in the future. Keefer said it would be reasonable for a stakeholder group to come back to the Legislature next year with a revised bill for inland and tidal waters that could be implemented within the five-year timeframe lawmakers have proposed.

“People have more questions than answers at this point and they don’t have a firm opinion because there hasn’t been time,” Keefer said.