Concerns continue as sea levels predicted to threaten nearly half of Maine’s beaches by 2050

A severe storm Monday night that resulted in over 100,000 power outages was followed by this winter’s first Nor’easter, which hit Maine on Saturday. The storms hammered Maine in the same week the Mills administration rolled out the state’s Climate Action Plan, Maine Won’t Wait, which outlines the need to address extreme storm and flooding events as a result of climate change.

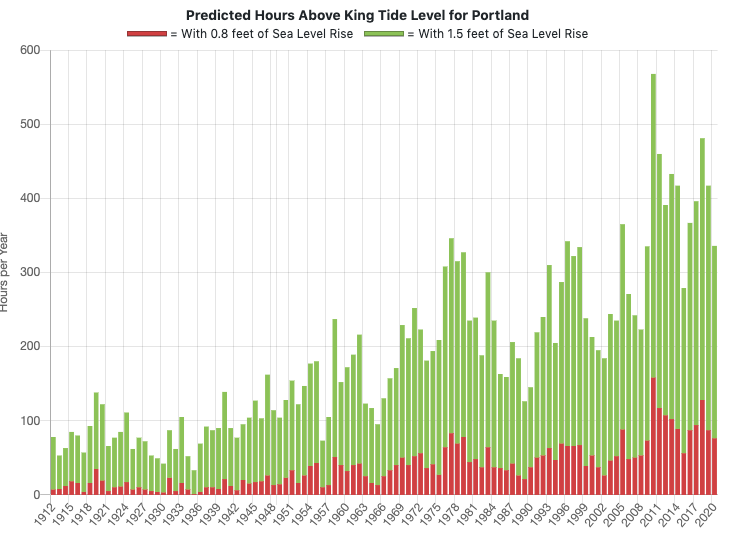

Portions of the report highlight worsening storm-surge flooding and coastal erosion in connection to rising sea levels along Maine’s coastline. The Maine Geological Survey released an interactive sea level rise ticker and dashboard on the heels of the Climate Action Plan this week to provide the public with short- and long-term data on rising sea levels and flooding occurrences.

Stephen Dickson, a marine geologist with the Maine Geological Survey, helped create the tracking tools and also co-authored the chapter on storm surges and sea level rise for the Maine Climate Council’s Science and Technology subcommittee. Since 2010, Dickson and his colleagues found that sea levels have inched further from their historical average.

“All of a sudden the water’s much higher than it’s been in the past,” said Dickson. “The water is creeping up slowly but surely.”

The data shows sea levels rising 0.8 feet by 2030 based on trends since 2000. An increase in sea level of 1.5 to 1.6 feet by 2050 would result in the loss of 40 percent of Maine’s beaches, Dickson said. The data also shows an increase in the number of hours of flooding experienced in Maine each year, which has huge economic repercussions.

“Unaddressed sea-level rise and repeated storm-surge flooding could cost Maine $17.5 billion in building damage from 2020 to 2050,” according to the Climate Action Plan. While storm-surge flooding is common with Nor’easters, a continued rise in sea levels could mean more flood damage from less severe storms.

“If we get a certain amount of storm surge, if the sea level is higher, it’s just that much more water that you would see from flooding,” said Michael Clair, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Gray. “It’s just kind of luck of the draw when storms hit.”

Clair and his colleagues forecast the weather on a weekly basis and watch for storms that coincide with high tide events — or astronomical tides — that happen monthly during a three- to five-day period when the moon is full and tides approach 10 feet.

The period of highest tides this month will occur from the 13th to the 17th, with tides expected to reach 11.6 feet on Dec.14 and 15.

“We’d be much more concerned if we were getting a storm around (Dec.) 14 and 15,” said Clair. When large storms coincide with astronomical high tide events, scientists fear flooding could be catastrophic.

“If we have another year or two where the winter sea levels are higher, that means that it’s a lot easier for the storms to cause flooding and to cause damage along the coast,” said Dickson. “(If) the timing of this peak in the storm surge happened at high tide, we could be in for a storm like we’ve never seen before.”

Dickson points to the Blizzard of 1978, which wiped out the pier at Old Orchard Beach with a large storm surge and a high tide that rose to 14.17 feet. More recently, Maine saw a storm in October 2019 that featured a four-foot plus storm surge that missed the high tide event by just a couple of hours.

Dickson sees the recent close calls as superstorm warning signs with the power to produce an event similar to Hurricane Sandy, which devastated the Atlantic coast in 2012, taking 233 lives and costing $70 billion in damages.

“(A superstorm) kind of could happen any day, it’s just a matter of chance,” said Dickson.