Knowing, battling domestic violence: The control factor

ROCKLAND — As Halloween decorations are packed away, so too are the costumes and masks. While masks are a familiar sight toward the end of every October, many women live every day within the mask of the "typical" family, when what lurks behind is more perilous than any campfire tale.

Domestic violence affects all ages, and runs the socio-economic spectrum. It is neither specific to religion nor education level.

The National Network to End Domestic Violence reported that seven million women are physically assaulted and/or raped by a current or former intimate partner every year.

One needs only to skim the local news to see domestic violence infractions dot almost every weekly blotter, including, but not limited to, threatening, harassment, terrorizing and physical violence.

One organization dedicated to supporting those affected by domestic violence is New Hope for Women, which serves Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox and Waldo counties.

Recently, Ellie Hutchinson, New Hope's Waldo County Community educator, and Amber Wotton, the director of New Hope's 'Time for Change' program, sat down to discuss some of the misconceptions about domestic violence.

While domestic violence almost always includes physical violence, there is also sexually-based abuse, which can include forcing a partner to engage in, or bear witness to, sexual acts beyond their personal boundaries.

There is also psychological abuse, such as threatening a partner, children and other family members with violence or slander. And, there is stalking and harassment.

Domestic abusers can try control partners by isolating them. This often begins slowly, with declarations of concern and wanting to keep a partner "safe.”

Over time, the behavior mutates into a systematic removal of every supportive relationship in a victim’s life, until one’s world has been whittled down to the four walls shared with their abusers.

Another common method of oppression that abusers use include legal and economic controls, according to Sanctuary for Families. This can manifest as threats of reporting illegal activity that may or may not actually be occurring or initiating legal proceedings spouses cannot afford to battle.

It can be easy to assume that anger is the prevailing force driving abusive partners, and that if only perpetrators of such violence learned better self-control, their domestic brutality would cease. But that is a myth both Wotton and Hutchinson dispel.

"There's a big difference between a bad temper and abuse," Wotton said. "We find that domestic abusers are able to be respectful in court, or to their probation and parole officers. They're able to be polite in front of extended family on Christmas. They are choosing to exert that control behind closed doors."

Both women agree that domestic abusers share little in common with even the most temperamental of partners.

When individuals with anger issues will often have criminal histories, including a variety of impulse-related charges, such as assault or disorderly conduct, it's not uncommon for domestic abusers to be regarded as upstanding citizens by other members of their community.

"Domestic violence is very calculated and very controlled, while a simple 'bad-temper' is not," Wotton said.

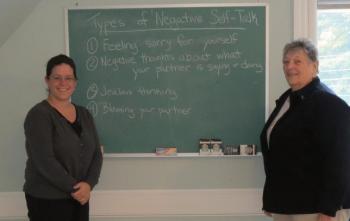

In a nondescript room in New Hope for Women's Rockland office, there is a weekly group that works to obliterate the beliefs that allow domestic violence to exist, and shine a spotlight on every brutal detail.

Run by Amber Wotton, the group focuses on working through the belief systems that support such a grim culture. From mandated counseling to anger management and other educational opportunities, there are a number of methods to end domestic violence.

One approach is a 48-week program that offers assistance to women affected by domestic violence. New Hope's Rockland office is also home to a 48-week program that teaches domestic abusers about the wide-reaching effects of their violence.

While Wotton says that they do see "some" self-referrals, she admits she has yet to see someone complete the program as a result of such motivation.

"We've had people come in and say, 'I haven't hit her yet, but I'm scared,'" she said. "I've had [those seeking help of their own volition] stay for 20-24 weeks [of the 48 weeks that constitutes successful completion of the program] and learn about power and control," she said.

Most often though, abusers are compelled to complete the program by figures in authority, such as a court ruling, or requirement from the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, Wotton said.

Self-referrals are uncommon, not simply due to the challenging nature of the program, but also, as Hutchinson notes, because: "most abusers don't see themselves as being abusive. Often what they're doing to their partners comes from a belief system."

"The 48 weeks, which although it seems long, is working to undo a lifetime of beliefs these individuals have," Wotton said. "If they haven't been asked to leave the program and have made it through, they are accountable by the end."

She said many people equate the program to Alcoholics Anonymous, where one can choose whether to participate. But that is not the case.

"It's not a forceful approach, but they're encouraged to participate and there are consequences if they choose not to," she said.

Wotton says it's generally clear whether or not participants are invested in the program.

"The people who are invested are doing hard work," she said. "They are supportive. They also will call each other out. There are people in class at all stages of the program and [those who have attended longer] are quick to call others out."

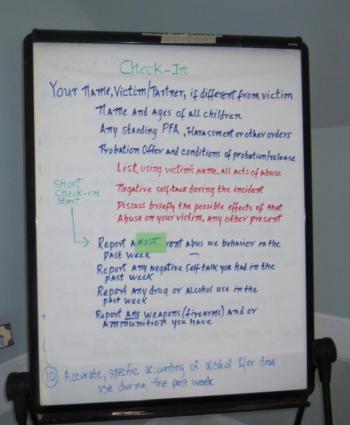

The first part of each class is a check-in designed to promote accountability.

"If someone says, 'she did this,' we won't have to say anything cause one of the other [particpants] will say, 'who?' and 'she didn't do that, you did that.'"

"It's a great dynamic," said Wotton. "That's the best way they learn, from each other."

Both Wotton and Hutchinson agree that the first six to eight weeks are the toughest, but: "Over time they see this isn't a punitive things where we're going to judge and hate them. We do this work because we want you to be happy, have a healthy family and for victims to be safe. We're in this for you."

Hutchinson agrees: "Think about some of the domestic-violence-related homicides you've read about. Many times, neighbors talk about what a 'good guy' the abuser was and express their surprise that the person would engage in such acts."

"That's the manipulative, cunning aspect of domestic violence," she said, "Often their public face is very important to them."

It's also one of the reasons it is vital for communities to be invested not only in punitive measures against domestic abusers, but also programs for the abused.

And, provide educational opportunities to offenders about choices they made, and consequences of those choices.

One such program, Time for Change, is run out of New Hope for Women's Rockland office (See sidebar).

Be an upstander, not a bystander

Domestic violence is frequently seen as a private problem.

The notion that responsibility to neighbors and friends stops once the door to home swings shut only emboldens abusers.

There are times when it can be difficult to discern whether or not an argument has turned physical, leaving citizens to wonder just when to alert authorities.

There can be a reluctance, or even fear of becoming involved, because it could become dangerous. But Hutchinson said domestic violence is always dangerous, "it's just a matter of who it's dangerous for."

For those who choose not to get involved because, 'what goes on behind closed doors should stay there,' Wotton also has a message: "Domestic violence can escalate quickly. If you hear something that doesn't sound safe or that sounds potentially abusive, it doesn't hurt to notify police, because if it's a healthy family that's not hiding anything, there is no harm in an officer checking in."

Quoting a teenage friend of her daughter’s, Wotton said: “Be an upstander, not a bystander. I think it's so important that that We do need to protect our neighbors, we do need to love our neighbors.

It's a sentiment Hutchinson agrees with.

"[Domestic violence] thrives on secrecy," she said. "You hear it time and time again, if there are children in abusive households they've been told 'you don't talk about this, at school or with anyone."

Erica Thoms can be reached at new@penbaypilot.com